Article Archive

Hermès

Equipage Géranium

29 November, 2015

Equipage is such a classic perfume that it’s tempting to ask why anyone would mess with it, but that’s a bit like wondering why anyone would want to reinterpret the Beatles’ original version of Yesterday.

Equipage is such a classic perfume that it’s tempting to ask why anyone would mess with it, but that’s a bit like wondering why anyone would want to reinterpret the Beatles’ original version of Yesterday.

Created by the perfumer Guy Robert and launched in 1970, Equipage was the first Hermès perfume to be designed specifically for men, and Robert composed a rich, subtly spicy scent which includes – among many other things – bergamot orange, jasmine, lily of the valley and clove-scented carnations.

Forty-five years on, the company’s in-house perfumer, Jean-Claude Ellena, has revisited three of its classics, in each case pairing them with a new ingredient. First came Bel Ami Vétiver, followed by Rose Amazone, and now we have his updated version of Equipage – Equipage Géranium.

If Ellena’s attempt to give Equipage a modern twist isn’t (to my nose at least) entirely successful, his choice of geranium (or pelargonium, to be botanically correct) as a new ingredient is a typically clever and imaginative one. Though the leaves of different species of pelargonium smell of everything from lemon to cinnamon, most of the so-called geranium oil used in perfumery comes from a single South African species, Pelargonium graveolens. As with all natural ingredients, geranium oil comes in a range of different grades, but they generally share a fresh, slightly sharp smell that’s usually described as both fruity and minty, often with a hint of rose.

I’m guessing that it was the fresh, minty element of geranium oil that appealed to Jean-Claude Ellena, and Equipage Géranium does smell a tiny bit fresher and sharper than the original Equipage – but it’s a subtle twist rather than a radical reinvention. I’m not sure it’s sufficiently different to make it worth choosing over the original, but unlike many of Ellena’s perfumes, which are always refined but sometimes stripped down until they’re slightly colourless, Equipage Géranium retains all the richness and complexity of its inspiration. Given the crude simplicity of so many modern scents, that’s a quality to be celebrated.

Edition Perfumes

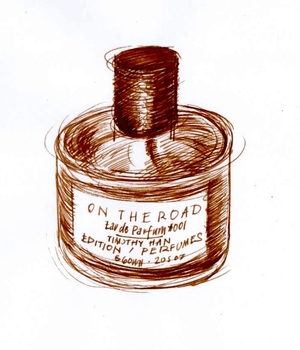

On the Road

26 November, 2015

Since it was published in 1957, Jack Kerouac’s amphetamine-fuelled road-and-head-trip of a novel has inspired generations of would-be counter-culturalists to take off into the unknown, but until now, it has never inspired a perfume.

Since it was published in 1957, Jack Kerouac’s amphetamine-fuelled road-and-head-trip of a novel has inspired generations of would-be counter-culturalists to take off into the unknown, but until now, it has never inspired a perfume.

On the Road is only the second scent from East London-based Edition Perfumes, aka perfumer Timothy Han, but it follows in the literary footsteps of his first fragrance, She Came to Stay. Inspired by Simone de Beauvoir’s 1943 novel L’Invitée, She Came to Stay went on to be a best-seller for legendary London fashion boutique Browns.

Taking the plotline of Kerouac’s novel as its starting point, On the Road is one of those rare things in contemporary fragrance: a scent whose story unfolds on the skin – unlike so many recent perfumes, which continue to smell boringly identical from first spritz to final dreary gasp.

As Han describes his perfume, ‘it begins with smoky notes of benzoin and birch reminiscent of the hot asphalt and grittiness of New York City. Punctuated by forays into tobacco-filled bars where a new era in music is being defined by the jazz greats, our journey takes us through the openness of the dusty cornfields of a Mid-Western America and rises to the cedar forests of a Pacific Coast. The restlessness of the journey finally gives way to the optimism left by the fresh green fragrance of galbanum, citrus and bergamot.’

That is quite a lot to squeeze in to a 60ml bottle of perfume, but what we like about On the Road is that it really does develop in the hours after first spraying it on your wrist. Its initial burst of smoke and whisky gradually evolves into a very pleasing, long-lasting woody vetiver. It’s a fine piece of work, and all the more impressive given the quality of the design and packaging – though perhaps that’s less surprising once you learn that Han started his career as an assistant to John Galliano.

Though Han develops and makes his fragrances in his Dalston studio himself, he sees his work very much as a collaborative effort, and for On the Road he’s keen to mention hot young chefs Olia Hercules and Oliver Rowe, Hixter bartender James Randall and model Olivia Inge, without whom its launch, in Han’s words, ‘would have been a no-go’.

But perhaps the biggest shout should go out to the ebullient London artist Cedric Christie, whose photographs from a train trip he took from New Orleans to New York add an authentically On the Road-ish touch to the perfume boxes. Buyers get to choose from five different pictures, adding an extra layer of depth and desirability to the scent. All in all it’s a great launch, and I’m very much looking forward to Timothy Han’s next novel in a bottle.

You must remember this

5 July, 2015

Do men and women smell perfumes differently? Of course they don’t. But the other day it struck me that many – and maybe most – men have a different relationship to perfume than women do, which affects the way they approach the whole subject.

One of the many clichés about perfume is the story, which gets recycled again and again, of how the (inevitably female) writer’s earliest scent memories were of the perfume that her mother wore. It’s a plausible enough story, I suppose, but after I’d read it a few times alarm bells started to ring.

I don’t think I’m a particularly unusual kind of chap, yet though I love perfume I don’t have any of those kinds of memories. My mum probably did wear perfume when I was growing up, just as she does now (and she smells very nice), but I don’t remember it making any kind of impression on me. And as for my dad, like the vast majority of dads when I was growing up (and I suspect still today), if he smelled of anything it was Imperial Leather, not Jicky or Cuir de Russie.

In fact the first perfumes I remember trying were when I was in my later years at school, and my introduction to them was through friends of my own age. In other words I don’t have that long, intimate familial relationship with fragrance that many women seem to have, and I suspect that’s fairly typical among men. Yet when I mentioned this to a female acquaintance it came as a complete surprise to her, and you’d certainly never realise it from what you read in the press.

My guess is that this may be one of the reasons why so many men find choosing and buying perfume so mystifying: they haven’t had the practise women have, or anyone to guide them or compare notes with from an early age. But maybe it’s my own upbringing that was unusual. It’d be interesting to hear what your own experience was.

Keep back

11 May, 2015

To the launch of a new range of perfumed bathing products from Hermès. Typically refined and beautifully packaged, but my favourite moment was being sprayed from head to foot by their glamorous Parisian press attaché in a ‘French shower’. Apparently that means I don’t need to wash for the following week or two…

Slugs and snails and puppy-dogs’ tails

23 April, 2015

A while back I attended a perfume training day with Roja Dove, perfumer extraordinaire in several senses of the word. A small group of us smelled something like a hundred different perfume ingredients, from bergamot to tuberose (the pure extract of which smells far more refined than any of the so-called ‘tuberose’ perfumes I’ve sampled).

Lots of surprises: extract of daffodil smells like hay; galbanum like freshly-podded peas. Fine lavender oil has an oddly sweaty side to it, which I think is one of the things I smell in Guerlain’s legendary Jicky. Roja brings in beaver glands, which gave us the wonderful leathery smell of castoreum (used in Chanel’s Cuir de Russie), and the greasy scrapings from the Ethiopian civet cat, which has the farmyard reek of fresh cow-pats but – in minute quantities – adds a disquieting hint of sex to any perfume in which it (or its synthetic equivalent) is used.

It was a fascinating and really useful day, though it must take daily practise to memorise so many ingredients. What surprised me, though, was the imprecision of perfume terminology. Particularly extracts come from very specific sources: galbanum, for example, derives from the roots of particular species of Iranian fennel (Ferrula gummosa and Ferrula rubricaulis), yet in our training day it was vaguely described as coming from ‘an umbellifer root’. Given that there are over 3,700 individual species in the umbellifer family (now renamed the Apiaceae), that wasn’t much help – cow-parsley is an umbellifer too, but I bet its roots don’t smell like fresh peas.

And as for daffodil smelling like hay, I wanted to know which daffodil: there are between 30 and 70 species of narcissus (the Latin term for daffodil) and hundreds and hundreds of varieties, many of which smell very different from each other.

It struck me as an odd contrast between how incredibly precise perfume chemists have to be, describing specific fragrances down to the molecular level, and yet how imprecise so much perfume terminology seems to be at the same time. If perfumers themselves use such vague descriptions, is it any wonder that we, the perfume-buying public, find the subject so confusing and so hard to understand?

Nothing succeeds like… nothing

14 April, 2015

Like many perfume lovers in London I spend a lot of time in Liberty, which has one of the best selections of perfume in the metropolis, covering everything from legendary classics to the latest obscure niche brand. Their staff are pretty good too: friendly and helpful, and generally more knowledgeable than your average department-store sales staff.

But it seems that even they aren’t entirely immune from the corrosive effect of marketing bollocks. According to Liberty’s beauty buyer Sarah Coonan, the store’s best-selling beauty product at the moment is Molecule 01, from cult company Escentric Molecules (yes, it’s meant to be spelled that way). Its gimmick is that it is, allegedly, entirely composed of a single chemical, called ISO E Super, which is normally used as an ingredient in other perfumes – Terre d’Hermès is a good example.

So far so boring. But what takes a gimmick into the realm of comedy is the marketing. On more than one occasion recently I’ve been minding my own nose in Liberty when a fellow customer has asked a sales assistant whether they stocked ‘that perfume that doesn’t smell of anything’. I’ve also, equally amusingly, heard a member of staff tell a customer something along the lines of ‘now this one is really special: it has no smell’.

OK, so you want to spend £30 on 30ml of a perfume that smells of nothing? That would be idiotic, wouldn’t it? But that’s what at least some people seem to want to believe, and what Liberty seem to be happy for people to go on believing.

As sales pitches go it’s one of the daftest on offer, but what I don’t like about it is that it’s not actually true. For Molecule 01 doesn’t smell of nothing at all. It might not smell of very much, and what it does smell of might not appeal to everyone (to me it smells mainly of photocopier fluid), but to tell credulous customers that it smells of nothing is surely just wrong.

As it happens, not even Escentric Molecules claim that Molecule 01 is odourless, though their sales shtick could hardly be described as hard sell. ‘Molecule 01,’ it reads, ‘is created solely from the aroma-chemical Iso E Super, which works as more of an effect than a fragrance. The scent has a subtle, velvety, woody note which will meld with your natural pheromones, vanish, then re-surface aftersome time, making it totally individual and personalised to the wearer. You will rarely smell this on yourself, Molecule 01 is more about the effect it has on others.’

Nonsense about pheromones aside, why anyone would want to spend good money on an, ahem, ‘effect’ that you can’t actually smell on yourself is slightly beyond me, though in fact there’s nothing unusual in a perfume that you can’t, after a while, smell on yourself. In fact that’s true of most perfumes, and if it wasn’t they’d probably drive you nuts.

So what, in the end, is special about Molecule 01? It’s a rather faint perfume that – like most perfumes – smells a bit different on different people, and that you can’t necessarily smell on yourself all the time. It’s not exactly the perfume equivalent of the Emperor’s new clothes, but it appears that a lot of people would like it to be. If nothing else it demonstrates the way that marketing and design can convince us of almost anything. Most intriguing.

Sock it to me

26 March, 2015

I was talking to a friend who has a fine turn of phrase, and she said something that made me think about why I wear perfume and what it means to me. ‘Perfume,’ she said, ‘it’s like new socks, isn’t it?’ And I know exactly what she means. Spritzing yourself with a favourite scent is just like wearing new socks or a new pair of trainers for the first time: it puts a bit of a spring in your step and sets you up for the day.

It also made me think about that old perfume cliché, the ‘signature scent’. Now, I’m all for finding a perfume that suits you and wearing it a lot, but it seems like such a shame to limit yourself to a single scent when there is such a rich and varied range of fragrances to choose from, old and new, relatively cheap and excruciatingly expensive. It’s nice to have a favourite shirt, of course, or a coat that always gets you compliments, but would you ever wear the same item of clothing every day, year in, year out? There are people out there, of course, who have a signature look, but let’s face it, they’re few and far between, and there’s a pretty good reason for that.

One of the joys of fashion is that all dressing, in the end, is about dressing up, and that means dressing for an occasion – whether it’s a party or a rainy day in June, a bitter winter’s day or the first warm week of spring. It’s fun to try new things on, and that’s precisely how I think of perfume too. There are perfumes for happy days and melancholy days, for summer days and winter days, for dates and dinner parties, for a nightclub or the opera. So why reduce your life to a single choice, when the world offers so many exciting possibilities?

Sex and scentsibility

4 February, 2015

Are you man enough to wear Chanel No. 5? Or woman enough to splash on Azzaro Pour Homme? I have to admit that I’ve never been a great fan of cross-dressing, but it makes about as much sense to talk about ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ fragrances as it does to talk about ‘male’ or ‘female’ art, music or food. The fact that we divide perfumes into men’s or women’s fragrances has less to do with logic than it has to do with marketing, packaging and conventional thinking – and if you look back it’s not even that old a distinction.

Once upon a time, perfumes were perfumes, and there appears to have been little in terms of a gender divide until the early twentieth century. Men wore fragrances which today we’d regard as outrageously effete: both Napoleon and Wagner were famous for drenching themselves in scent, and Victorian gentlemen favoured sweetly scented floral perfumes alongside the ubiquitous eau de cologne. Even the words themselves – fragrance, perfume, scent – are genderless: the daft male-only term ‘after-shave’ appears only to have been dreamed up in the 1920s as a marketing wheeze. Though the expression may have made perfume sound a bit more butch and manly, all too often (in the days before male moisturiser became acceptable) it also left the more literal-minded chap with a burning face and peeling skin.

I’m not suggesting that male readers should rush out and purchase the olfactory equivalent of a pair of pink frilly knickers. Some scents (naming no names) are so insanely sweet and girly that it would be hard for even the most rugged male to get away with wearing them, but then they also tend to be the kind of perfume that smell as terrible on a grown woman as they would on any self-respecting man.

Beyond those parodies of perfume, there are remarkably few fragrances that, if you trust your nose and can brace yourself to ignore everything you’ve been told by breathless adverts and terrifyingly made-up sales assistants, are so incontrovertibly feminine or masculine as to be completely unwearable by either sex. Take one famous example. Christian Dior’s Eau Sauvage was launched in 1966 and quickly established itself as a hugely popular men’s fragrance. It’s stayed on the best-seller lists ever since, and I think most men would agree that there are few more bracing, fresh and (above all) masculine fragrances around.

I couldn’t agree more, but if you’re a fan of Eau Sauvage, next time you’re in a well-stocked perfume store, wander over to the women’s-perfume counter and have a smell of Diorella, launched just six years later and designed by the same perfumer, the legendary Edmond Roudnitska. The first time I smelled it I thought, ‘But this is Eau Sauvage!’ And it is, give or take some extra fruitiness which, you could say, gives it a slightly more girly character – though perfume guru Luca Turin regards it as ‘a perfected Eau Sauvage and one of the best masculines money can buy’.

In many ways it’s even easier the other way around, and women seem always to have been less inhibited about adopting fragrances that were originally intended to be for the opposite sex. Eau Sauvage is a classic example: whether they smelled it on their boyfriends or discovered it for themselves, women quickly recognised it as the masterpiece it is, and those in the know have been wearing it ever since. Guerlain’s superb Vetiver is, to my mind, one of the most archetypically masculine perfumes in existence, yet it, too, has long been a female favourite – the olfactory equivalent of an Yves Saint Laurent tuxedo.

More striking still are those fragrances that have crossed the gender divide more or less entirely. When Aimé Guerlain launched Jicky in 1889, it was initially bought by men; at the time its sharp, slightly catty smell was considered too overtly sexual in character for respectable women to risk wearing it. By the 1920s, though, liberated by the rise of female emancipation, women started using Jicky too, and gradually it became a ‘female’ fragrance – though a few self-confident men (Sean Connery being the most often-cited example) continue to wear it today. Chanel’s super-plush Cuir de Russie followed a similar trajectory, though it would be hard, even now, to define it as either masculine or feminine in character.

Visit the standard-issue perfume store and you’d be forgiven for thinking that we were still stuck in a world where men were men and women were women and never the twain should meet, as if history – in the world of perfume at least – had got stuck around 1955 and all the social and sexual revolutions since then had never actually happened. But society, of course, has changed, and there are encouraging signs that at least parts of the perfume industry have begun to realise that dividing fragrance along crude gender lines is a weirdly outdated thing to do. A handful of future-looking perfume brands, such as Byredo, Comme des Garçons and Escentric Molecule, already offer ‘genderless’ fragrances, and there is a growing trend for imaginative retailers to follow their lead, stocking perfumes by brand instead of dividing them into men’s and women’s scents.

Perfume customers are changing too. The majority of people may continue (for the moment at least) to accept the status quo, but for the small but growing band of perfume-lovers who are happy to think for themselves, choosing perfume on the basis of its supposed masculinity or femininity has come to seem increasingly outmoded. The trick is simply to follow your nose: to choose the perfumes you love, like the people you love, regardless of what other people might say.

Burnt out

1 February, 2015

Just back from yet another home-fragrance launch. Nice people, perfectly nice products, but does the world really need more reed diffusers and scented candles? (For that matter, does the world really need any reed diffusers and scented candles? But that’s another question.)

Go into a big department store today and it sometimes feels like there are whole floors given over to home fragrance: rack after rack of virtually identical products and virtually identical scents. How does anybody choose? And who is buying all this stuff?

What I can’t get my head round is why anyone feels it’s worth launching yet another brand in such a super-saturated marketplace. Starting a company and creating new fragrances takes a big investment, and making your money back must be increasingly tough. But there again maybe it’s an easy way to make big profits, and I’m simply not in the know.

The people I met today obviously felt that their products were sufficiently different to stand out from the crowd, but a weary feeling of familiarity washed over me as they described the ‘story’ behind each scent, complete with misspelled press-releases. I’ve seen it all so many times before. Just please don’t buy me a scented candle for my birthday.

Hidden beauty

15 November, 2014

This autumn, while I was staying in the south of France, I got the chance to visit what you could think of as the holy grail of the perfume industry: IFF-LMR (aka Laboratoires Monique Rémy), outside Grasse. These days the town is a minor player on the global stage, mostly trading on its past as the one-time centre of French perfumery, but it still has a few small manufacturers, including IFF-LMR, which makes some of the world’s finest and most expensive natural perfume ingredients.

Not that there’s much to see from outside. The Parc Industriel Les Bois de Grasse is about as exciting as any other industrial estate I’ve visited (ie not very exciting), with a collection of anonymous-looking warehouses and bland office blocks scattered around a series of wide, empty roads that sweep between the pine trees of the bois. IFF-LMR’s exterior is no different from the rest, and to be frank its interior isn’t much more thrilling: an open-plan office above a double-height warehouse, with modestly sized manufacturing and research areas beyond that.

Everything – the vinyl floors, with gentle ramps at each exit to contain accidental floods, the stainless-steel pressure vessels, the glass tubing – is shiny and spotlessly clean. ‘We’re certified to food hygiene standards,’ explains managing director Bernard Toulemonde, who is understandably proud of the place; all part and parcel of their emphasis on purity and precision.

One other thing makes IFF-LMR feel immediately different from most factories I’ve visited: the smell. Instead of the usual scent of sump oil and burning electricity, there’s a faint but pervasive fragrance in the air, which could be rose or could be lavender but is most likely an atmospheric amalgam of those and all the other delicious perfume ingredients they extract.

Though it’s the machines, if you like, that symbolise the factory’s beating heart – glass alembics, ice-encrusted condensers, basic-looking but baffling computer consoles – for me the most exciting part was the sealed, chilled storeroom where the extracts themselves are kept, in stainless-steel containers, some the size of Thermos flasks, others in small steel drums.

Stored in alphabetical order, as far as we could ascertain (Bernard was no surer than I was), they’re ranged on shelf after shelf, with a perfume-poem of names: Basil Oil Grand Vert, Blackcurrant Bud Absolute Burgundy, Castoreum Absolute, Cinnamon Essential, Galbanum Resinoid, Hay Absolute, Labdanum Resinoid, Narcisse Absolute French, Orange Bigarade Oil, Orris Concrete, Osmanthus Absolute, Rose Ultimate Extract, Vetiver Heart – the shelves go on and on.

But for me the most fascinating aspect of their work, as a plant-grower and earth-digger myself, is the fact that IFF-LMR is as much about agriculture as it is about perfumery – Bernard Toulemonde is a professional agronomist, and he and his staff spend much of their time in fields around the world, from France to Madagascar, Egypt to Haiti, working with local farmers to grow the healthiest, most productive crops of fragrant plants that can then be processed and refined back at the factory, or in their larger processing plant in Spain. That, to me, is the essence of perfume: a magical blend of nature and science – something we watched as raw rough lavender oil was distilled into the clearest, most delicately perfumed liquid.

Sadly, though understandably, photography is not allowed, or I’d have been able to share them with you, but you can see a few on their website here. One day I hope to return to see some of their ingredients being grown and harvested.