Article Archive

Christian Dior

Eau Sauvage

3 March, 2014

How did I get this far without reviewing Eau Sauvage? And now that I’ve finally got round to reviewing it, how am I going to do justice to such an iconic perfume? OK, I’ve covered Eau Sauvage Extrême, but that’s a dreary spin-off and bears little relation to the glorious real thing. So, deep breath now, and here we go.

How did I get this far without reviewing Eau Sauvage? And now that I’ve finally got round to reviewing it, how am I going to do justice to such an iconic perfume? OK, I’ve covered Eau Sauvage Extrême, but that’s a dreary spin-off and bears little relation to the glorious real thing. So, deep breath now, and here we go.

Created by the legendary perfumer Edmond Roudnitska, Eau Sauvage was launched in 1966, and it’s deservedly regarded as one of the greatest men’s perfumes of all. Roudnitska’s took the idea of a classic men’s cologne, packing it full of fresh, zingy, clean-smelling bergamot-orange oil from southern Italy, but then he did a brilliant thing, by blending it with an equally strong dose of a recently patented chemical called Hedione.

Hedione smells of jasmine – as well it might, since it was discovered by chemists during the process of deconstructing the molecular bits and bobs that, collectively, create natural jasmine’s heady, narcotic scent. Hedione’s real name is methyl dihydrojasmonate, and it was first isolated in 1958 by Dr Edouard Demole, who worked for the giant Swiss perfume company Firmenich.

Methyl dihydrojasmonate has a light jasmine smell but also something citrusy about it, giving Edmond Roudnitska a jigsaw piece that fitted into both the bergamot orange of a man’s cologne, and also had something – but crucially not too much – of natural jasmine’s sumptuous, powerfully floral scent, which most men would have considered far too feminine to wear.

To this Roudnitska added lavender – another floral scent, though this time one whose herby, faintly sweaty character had made it a long-standing male favourite – as well as a range of other, less pronounced ingredients including oakmoss (originally extracted from a lichen that smells of forests after rain) and patchouli, which in small amounts, I’m guessing, enhances the dandified character of Eau Sauvage without pushing it over into full-on let-it-all-hang-out hippiness.

A great perfume is one thing, and an all-too-rare thing at that, but it’s rarer still for a brilliant perfume to be supported by great marketing and presented in a great bottle. And here Eau Sauvage struck lucky again. Christian Dior died in 1957 of a heart attack, but under Yves Saint Laurent and then Marc Bohan, the company commissioned a series of sexy, tongue-in-cheek yet effortlessly elegant posters from René Gruau, arguably the greatest fashion illustrator of the 20th century. They certainly added to Eau Sauvage’s masculine appeal.

Few of us think a great deal about the bottles that contain the perfume we use, though they do have their collectors (most of whom, oddly, seem to have lost interest in the perfumes they contain). But some bottles repay a second glance, and Eau Sauvage is one of them. It was designed by Pierre Camin, who worked for Baccarat and created many of the bottles for the perfumer François Coty, and its chic silver cap, embossed with a pattern of tiny overlapping scales like a freshly-caught mackerel, is said to have been inspired by the silver thimble that Christian Dior always had to hand. The diagonally ridged sides of the bottle itself, meanwhile, are supposed to resemble the regular pleats of a Dior dress, though that seems a bit of a stretch to me.

I could go on, but in the unlikely event that you’ve never smelled Eau Sauvage, or think of it as a tired old dinosaur, I’d rather you headed out and tried it for yourself. Just be careful, though, as Dior have experimented with different versions over the years, and what’s now called Eau Sauvage Extrême (which you’d think would just be a stronger version, as indeed it used to be) is now a completely different fragrance, pleasant enough in a dull way but far less exciting than the original.

My last words, though, go to Edmond Roudnitska, not only because he was a perfumer of genius, but also because he also had something so important to say about marketing that it should be tattooed on the forehead of every perfume-company PR.

‘The choice of a perfume,’ he said, ‘can only rest on the competence acquired by education of olfactive taste, by intelligent curiosity and by a desire to understand the WHY and the HOW of perfume. Instead, the public [is] given inexactitudes and banalities. The proper role of publicity is to assist in the formation of connoisseurs, who are the only worthwhile propagandists for perfume, and it is up to the perfumers to enlighten, orient and direct the publicity agents.’

Here’s to the day his dream comes true.

Architectural scent

22 January, 2014

To the preview of the Royal Academy’s new ‘Sensing Spaces: Architecture Reimagined’ show. More, perhaps, of an adult’s (and children’s) playground than a seriously thought-provoking show, but I was very taken with an installation by the Japanese architect Kengo Kuma, designer (among other things) of the LVMH head office in Tokyo.

In two darkened rooms, Kuma has installed rather beautiful pyramidal sculptures using willowy slivers of bent bamboo, lit by tiny spotlights in the floor. I wouldn’t exactly class it as architecture myself, but what really appealed to me was Kuma’s imaginative use of scent. The first, larger sculpture is impregnated with the smell of hinoki, the fragrant Japanese cedar (Chamaecyparis obtusa), traditionally used in the construction of temples, while the second room evokes the grassy, hay-like smell of new tatami mats.

The scent of buildings is often overlooked, so it’s refreshing to come across an architect who values smell as much as the other senses. Other architects please take note.

She’s lost control again

7 April, 2013

I’ve started introducing myself to some of the professionals in the perfume industry, which so far has been really encouraging: everyone’s said positive things about The Sniff Box, but just one comment caught me slightly up short.

I’d been talking to someone who I guess you could call an important player in the perfume world. She’d been complimentary about my attempts to write about perfume in a straightforward, easily accessible way, but when I asked her what she thought of my illustrations, she paused then said, ‘I think you could find that some of the perfume companies might have a problem with them.’

In fact none of the brands I’ve talked to so far have ‘had a problem’ with them, but I thought that was such an interesting thing to say, and rather revealing too.

Perfume brands, just like their compatriots (and sometimes owners) in the fashion world, spend vast amounts of money and effort on creating an image for their brand, which often disguises the fact that there’s really very little to distinguish one brand from the next. So much of the perfume and fashion industry’s profits, in the end, are about mystique, and mystique is a fragile and evanescent thing.

Brand building is all about control, in the end: control of your brand’s image, and anything that might dent that image in any way is a threat – which is why big brands are often so litigious.

The problem (looked at from a brand-manager’s point of view) is that little thing called freedom of expression. You can police your brand as fiercely as the KGB, but once it’s out in the public domain there’s little you can do about people’s opinions apart from muttering vague threats and taking legal action if they do something rude with your logo.

It’s all very Wizard of Oz, when you come to think of it. You remember how (plot spoiler warning!) the wonderful wizard is finally revealed to be a very unimpressive little man cranking away on a lot of levers, all hidden away behind a curtain?

Most branding works on exactly the same smoke-and-mirrors principle, and a lot of brands are terrified that the rest of us (the consumers, as we’re so dismissively called) might one day see behind the curtain and realise how we’ve had the wool pulled over our eyes. Ideally they’d prefer us to repeat what they say about their products and always to use the pictures they provide – which is why, I think, I was told that drawing perfume bottles might be ‘a problem’.

But actually I think that seeing behind the curtain is a great thing, as long as there’s something interesting behind it. And I also think that the more people know about something, the more interested in it they’re likely to be. Create a great brand and great products and brand managers have nothing to fear.

Yves Saint Laurent

M7

12 July, 2012

Tom Ford’s relatively short tenure at Yves Saint Laurent, from 2000 to 2004, won him both fans and detractors – among them YSL himself, who used to pen helpful letters criticising Ford’s latest shows. But it was Ford’s own considerable design talents and his genius for publicity dragged the declining fashion house back into the limelight, no more so than with the launch of M7 in 2002.

Tom Ford’s relatively short tenure at Yves Saint Laurent, from 2000 to 2004, won him both fans and detractors – among them YSL himself, who used to pen helpful letters criticising Ford’s latest shows. But it was Ford’s own considerable design talents and his genius for publicity dragged the declining fashion house back into the limelight, no more so than with the launch of M7 in 2002.

In a nod to Jeanloup Sieff’s legendary 1971 photograph of a naked Yves Saint Laurent that was used to promote the first YSL men’s fragrance, Ford launched M7 in 2002 with a full-frontal nude of martial-arts star Samuel de Cubber shot by Swedish photographer Sølve Sundsbø.

The all-too predictable storm of controversy may have long since been left behind, and sadly the perfume has since been reformulated and dumbed down, which is a real shame as it was originally an unusual and (to me at least) extremely appealing scent.

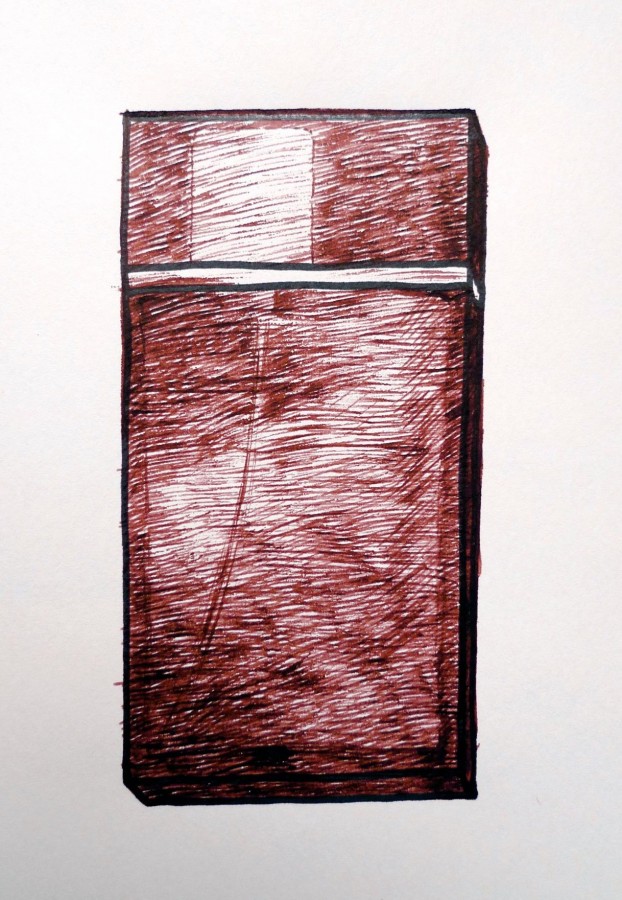

Tom Ford’s influence is most obviously apparent with the original bottle (pictured), which was a crisply designed rectangle of brown glass, the colour of medicine bottles. The brown perspex cap clipped on with a satisfying clunk, and the spray mechanism was set two-thirds along the top, giving it a cool asymmetric outline which has ‘designer’ written all over it. (Not literally – keep up!) It’s since been redesigned and the perfume reformulated, which is sadly typical of the industry.

What makes the perfume itself immediately striking is its odd yet somehow very successful combination of fruity sweetness with the almost catch-in-the-throat smell of woodsmoke, which gives it a masculine edge it would otherwise lack. Not very noticeable is an initial burst of citrus provided by bergamot and mandarin, though that probably adds something to that first impression of fruitiness.

What I hadn’t realised was that perfumers Alberto Morillas and Jacques Cavallier also added a touch of rosemary to the mix. It’s not something that jumps out at you, but smelling it again I twigged, for the first time, that rosemary’s herby smell has something a bit smoky about it too.

It’s a very clever way to emphasise this fragrance’s appealing smokiness, whose dryness is also underlined by a touch of that ultimate in male-perfume ingredients, the bitter earthy smell of vetiver. M7 lasts well too, and if some people find it either too fruity or slightly medicinal, then let them; I really don’t care.