Tagged With ‘castoreum’

Slugs and snails and puppy-dogs’ tails

23 April, 2015

A while back I attended a perfume training day with Roja Dove, perfumer extraordinaire in several senses of the word. A small group of us smelled something like a hundred different perfume ingredients, from bergamot to tuberose (the pure extract of which smells far more refined than any of the so-called ‘tuberose’ perfumes I’ve sampled).

Lots of surprises: extract of daffodil smells like hay; galbanum like freshly-podded peas. Fine lavender oil has an oddly sweaty side to it, which I think is one of the things I smell in Guerlain’s legendary Jicky. Roja brings in beaver glands, which gave us the wonderful leathery smell of castoreum (used in Chanel’s Cuir de Russie), and the greasy scrapings from the Ethiopian civet cat, which has the farmyard reek of fresh cow-pats but – in minute quantities – adds a disquieting hint of sex to any perfume in which it (or its synthetic equivalent) is used.

It was a fascinating and really useful day, though it must take daily practise to memorise so many ingredients. What surprised me, though, was the imprecision of perfume terminology. Particularly extracts come from very specific sources: galbanum, for example, derives from the roots of particular species of Iranian fennel (Ferrula gummosa and Ferrula rubricaulis), yet in our training day it was vaguely described as coming from ‘an umbellifer root’. Given that there are over 3,700 individual species in the umbellifer family (now renamed the Apiaceae), that wasn’t much help – cow-parsley is an umbellifer too, but I bet its roots don’t smell like fresh peas.

And as for daffodil smelling like hay, I wanted to know which daffodil: there are between 30 and 70 species of narcissus (the Latin term for daffodil) and hundreds and hundreds of varieties, many of which smell very different from each other.

It struck me as an odd contrast between how incredibly precise perfume chemists have to be, describing specific fragrances down to the molecular level, and yet how imprecise so much perfume terminology seems to be at the same time. If perfumers themselves use such vague descriptions, is it any wonder that we, the perfume-buying public, find the subject so confusing and so hard to understand?

Chanel

Antaeus

8 December, 2014

When I first started thinking about The Sniff Box, I wondered how I could make it look different from other perfume blogs. I knew I’d have no problem with the overall look, thanks to my super-talented friend, Leanda Ryan, whose design perfectly reflects the idea of ‘perfume in plain English’.

When I first started thinking about The Sniff Box, I wondered how I could make it look different from other perfume blogs. I knew I’d have no problem with the overall look, thanks to my super-talented friend, Leanda Ryan, whose design perfectly reflects the idea of ‘perfume in plain English’.

But illustrating individual perfumes is a problem, as you’ll gather if you look at other perfume sites on the interweb. The obvious thing to do is to use a ‘pack shot’, generally supplied by the brand in question: it’s what the brands like as that’s how they want you to see their scent, but how many times do you want to see the same cheesy photograph?

The trouble is, if you don’t use a photo of the bottle, what can you use instead? How do you illustrate something you can smell but can’t actually see? It’s interesting to check out what other people come up with, but given that few bloggers can afford to commission photography or illustration, they’re generally stuck with stock shots of things like perfume ingredients – a sprig of lavender, say, or a twist of lemon – which are as cheesy as the pack shots they’re trying to avoid.

It took a while, but finally it struck me: since I can draw, after a fashion, why not draw my own illustrations? And that’s how I began.

All of which is a roundabout way of saying that, when I was trying to draw my bottle of Antaeus this morning, it gradually dawned on me that it is one of the most beautiful perfume bottles I know. It’s also one of the simplest: a tall, square, black-glass container that, if you took away the classy sans-serif Chanel lettering, would bear a more-than-passing resemblance to sinister monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Designed (or at least commissioned) by Chanel’s long-standing artistic director, Jacques Helleu, and launched in 1981, Antaeus was a kind of dark-side twin to the brand’s only other men’s fragrance at that time, Pour Monsieur (launched way back in 1955). Their bottles may be almost identical in shape, but Pour Monsieur is as cool and transparent as Antaeus is brooding and mysterious, and that reflects the fact that they’re very different scents.

Pour Monsieur is a refined, impeccably discreet fragrance: perfect in its way but perhaps (dare one whisper it?) just a tiny bit dull. Antaeus, by contrast, is a dark sexy scent that was launched just as the disco era crashed and burned: the same year Ian Schrager and Steve Rubell sold out of Studio 54 and the big disease with a little name first reared its ugly head.

Antaeus (the scent) was created by Chanel’s much-fêted in-house perfumer, Jacques Polge, in collaboration with François Damachy, now head of fragrance at Dior). As suggestive as Pour Monsieur is safe, its sexiness comes from castoreum, derived from a secretion extracted from beaver wee (I kid you not), which despite its revolting origins becomes, after careful treatment, a potent perfume ingredient, with its musky, leathery smell.

It’s a warm, slightly spicy leather scent, with a lot of Mediterranean herbs, most notably clary sage and thyme, that most of us would probably associate with hot, rocky mountainsides in southern France and Greece. My nose isn’t yet sensitive enough to identify them, but it also apparently contains labdanum (derived from two different species of Cistus, another Mediterranean shrub), as well as sandalwood and patchouli, which presumably add to the slightly hippyish warmth of the scent.

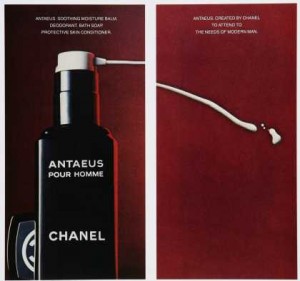

Antaeus became a big best-seller in the early 1980s initially, it seems, among gay men, and with its hints of sex and leather it’s easy to see why. Chanel itself tapped into this trend in 1983 with a delightfully pervy advert (pictured), whose subtext I can leave to your imagination.

Antaeus became a big best-seller in the early 1980s initially, it seems, among gay men, and with its hints of sex and leather it’s easy to see why. Chanel itself tapped into this trend in 1983 with a delightfully pervy advert (pictured), whose subtext I can leave to your imagination.

But gay men, as we’ve often been told, are classic early adopters, and these days Antaeus is just as likely to attract anyone who enjoys a rich and complex scent. It’s long been one of my favourites, for its warmth and easy appeal, but I love its darker origins too: sex (and history) in a bottle.

Different Company

Osmanthus

8 July, 2014

Much excitement in Weymouth, as the old Woolworth’s site has been transformed into a branch of T.K.Maxx. Even more excitement when, on our first visit, what should I pluck from the trashy mass-market scents you’d expect to find in a discount outlet but a brand-new bottle of Osmanthus by The Different Company.

Much excitement in Weymouth, as the old Woolworth’s site has been transformed into a branch of T.K.Maxx. Even more excitement when, on our first visit, what should I pluck from the trashy mass-market scents you’d expect to find in a discount outlet but a brand-new bottle of Osmanthus by The Different Company.

What a highly collectible perfume by a fairly obscure, high-end brand was doing in the Weymouth branch of T.K.Maxx I have no idea, but there it was, ours for the princely sum of £16.99 (recommended retail price €142).

Created by the much-admired perfumer Jean-Claude Ellena (now the in-house perfumer for Hermès) for the company he founded in 2000, Osmanthus gets an admiring review in the even more widely admired Perfumes: The Guide by Luca Turin and Tania Sanchez, and you can see why.

It’s a gentle, sweet but subtle scent, whose plush peachy centre is reminiscent of Guerlain’s timeless Mitsouko, though it seems to lack either Mitsouko’s strength of character or its mysterious staying-power. Yet Osmanthus has magic of its own, and its apparent evanescence on the skin proves something of a disappearing trick – for after putting a little on the back of my hand and noting that it didn’t seem to last very long, what should happen but that an hour or two later, as if from nowhere, its fresh, fruity scent would suddenly snap into focus again, almost as strong as when I first sprayed it on.

I’ve no idea how it’s done, or even whether the effect was intentional, but my guess is that it’s got something to do with the way Osmanthus’ peachiness bonds with the perfume’s other elements, some of which are a little surprising, like castoreum, a resinous compound extracted from beavers that has a leathery, animalic smell and is also found in Chanel’s wonderful Cuir de Russie.

Natural osmanthus, incidentally, is an attractive evergreen shrub which, in sheltered conditions, will grow to the size of a small tree. It grows wild in the Himalayas, China and Japan and was first introduced to European gardens in 1771, where it became known as Sweet Tea or Fragrant Olive. In the autumn it bears thousands of small but intensely fragrant white flowers, whose intoxicatingly sweet scent gives the plant its botanical name, Osmanthus fragrans.

Its fragrance, indeed, is remarkably powerful, as we discovered on an autumn visit to the enchanted garden of Brécy, near Bayeux. From the massively stepped levels of the formal gardens, which form a kind of vast single staircase up towards the Normandy sky, we recognised osmanthus’ heady scent a long time before we finally located its source, from a couple of dark columnar trees planted close against the south wall of the church, outside the gardens themselves.

Despite the sheer intensity of its fragrance, this is one of the only powerfully sweet scents I know that one can never smell enough (unlike, say, Madonna lilies, whose scent becomes overwhelming after a while): there’s a fresh lemony edge to osmanthus that makes it refreshing and intoxicating all at once. Enjoy Jean-Claude Ellena’s perfume by all means, but plant the tree wherever you can.