Tagged With ‘labdanum’

Heeley

Phoenicia

24 August, 2015

Though there’s some dispute about its exact origins, the word ‘perfume’ most likely derives from ‘fumes from a substance being burned’, so you could say that Phoenicia, the latest fragrance from Yorkshire-born, Brussels-based perfumer James Heeley goes back to perfume’s roots.

Though there’s some dispute about its exact origins, the word ‘perfume’ most likely derives from ‘fumes from a substance being burned’, so you could say that Phoenicia, the latest fragrance from Yorkshire-born, Brussels-based perfumer James Heeley goes back to perfume’s roots.

The name refers to the ancient civilisation that flourished in the eastern Mediterranean around 1000BC, but Phoenicia’s smell is instantly evocative of childhood bonfires, just as his earlier L’Amandière evokes an almond orchard in spring.

‘I loved the way my hair smelled after a bonfire,’ Heeley recalls, and he’s captured the memory using a mixture of cedarwood, oud, smoky birchwood and vetiver.

Luckily there’s more to Phoenicia than smoke. ‘I’ve always loved the concrete of labdanum ciste,’ Heeley says (the densest refined extract from the fragrant Mediterranean shrub Cistus ladanifer), ‘which has a slight smell of dates or prunes.’ Adding this to the formula gives Phoenicia an attractive hint of dried-fruit sweetness, which balances the smokiness is a very attractive way. It certainly lights my fire.

Chanel

Pour Monsieur

7 July, 2015

I’ve loved Pour Monsieur for decades now, so it was a bit of a surprise when I realised that I hadn’t reviewed it up till now. But actually I think that tells you something about the fragrance itself, which is so discreet that it’s all too easy to overlook – and that’s a real shame, because it’s a wonderful thing.

I’ve loved Pour Monsieur for decades now, so it was a bit of a surprise when I realised that I hadn’t reviewed it up till now. But actually I think that tells you something about the fragrance itself, which is so discreet that it’s all too easy to overlook – and that’s a real shame, because it’s a wonderful thing.

Pour Monsieur smells softly spicy when you first spray it on, but soon you also start smelling its mossy, herbaceous base. The spiciness comes partly from cardamom, and the woodiness is a mixture of oakmoss (actually a type of fragrant lichen) with tiny amounts of cedarwood, resinous labdanum (a kind of cistus) and earthy vetiver.

Chanel’s first modern men’s fragrance, it was conjured up by the perfumer Henri Robert and launched in 1955. Robert, who was born in 1899 and died in 1987, took over at Chanel after the retirement of the legendary Ernest Beaux, and went on to launch Chanel No19 in 1970 and Cristalle in 1974.

Pour Monsieur is one of the best examples of the perfume style or ‘family’ known as chypre, which derives from the French for Cyprus (the island rather than the tree), presumably inspired by the scent of Mediterranean herbs and shrubs baking in the sun. The basic combination – first popularised by François Coty in a 1917 perfume of the same name – combines bergamot, oakmoss and labdanum.

There have been endless variations on the theme since, but few of them match Pour Monsieur for sheer class; even its packaging is beautifully cool. Though it’s not an expensive perfume, it is redolent of luxury in its quiet complexity, like the deceptively simple face of a Patek Philippe watch. This is insider luxury, if you like, which is all about discretion and restraint rather than ostentation and excess.

The upside – in a perfume or a Patek Philippe – is that not everyone will recognise what you’re wearing. And while Pour Monsieur lasts a long time on the skin, it’s one of those fragrances that doesn’t carry far, so if you’re looking to impress it probably isn’t for you. But if wearing something wonderful makes you feel more self-confident and assured, then I can think of few better perfumes to buy.

Chanel

Antaeus

8 December, 2014

When I first started thinking about The Sniff Box, I wondered how I could make it look different from other perfume blogs. I knew I’d have no problem with the overall look, thanks to my super-talented friend, Leanda Ryan, whose design perfectly reflects the idea of ‘perfume in plain English’.

When I first started thinking about The Sniff Box, I wondered how I could make it look different from other perfume blogs. I knew I’d have no problem with the overall look, thanks to my super-talented friend, Leanda Ryan, whose design perfectly reflects the idea of ‘perfume in plain English’.

But illustrating individual perfumes is a problem, as you’ll gather if you look at other perfume sites on the interweb. The obvious thing to do is to use a ‘pack shot’, generally supplied by the brand in question: it’s what the brands like as that’s how they want you to see their scent, but how many times do you want to see the same cheesy photograph?

The trouble is, if you don’t use a photo of the bottle, what can you use instead? How do you illustrate something you can smell but can’t actually see? It’s interesting to check out what other people come up with, but given that few bloggers can afford to commission photography or illustration, they’re generally stuck with stock shots of things like perfume ingredients – a sprig of lavender, say, or a twist of lemon – which are as cheesy as the pack shots they’re trying to avoid.

It took a while, but finally it struck me: since I can draw, after a fashion, why not draw my own illustrations? And that’s how I began.

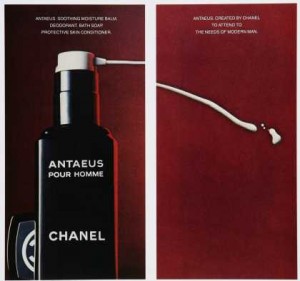

All of which is a roundabout way of saying that, when I was trying to draw my bottle of Antaeus this morning, it gradually dawned on me that it is one of the most beautiful perfume bottles I know. It’s also one of the simplest: a tall, square, black-glass container that, if you took away the classy sans-serif Chanel lettering, would bear a more-than-passing resemblance to sinister monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Designed (or at least commissioned) by Chanel’s long-standing artistic director, Jacques Helleu, and launched in 1981, Antaeus was a kind of dark-side twin to the brand’s only other men’s fragrance at that time, Pour Monsieur (launched way back in 1955). Their bottles may be almost identical in shape, but Pour Monsieur is as cool and transparent as Antaeus is brooding and mysterious, and that reflects the fact that they’re very different scents.

Pour Monsieur is a refined, impeccably discreet fragrance: perfect in its way but perhaps (dare one whisper it?) just a tiny bit dull. Antaeus, by contrast, is a dark sexy scent that was launched just as the disco era crashed and burned: the same year Ian Schrager and Steve Rubell sold out of Studio 54 and the big disease with a little name first reared its ugly head.

Antaeus (the scent) was created by Chanel’s much-fêted in-house perfumer, Jacques Polge, in collaboration with François Damachy, now head of fragrance at Dior). As suggestive as Pour Monsieur is safe, its sexiness comes from castoreum, derived from a secretion extracted from beaver wee (I kid you not), which despite its revolting origins becomes, after careful treatment, a potent perfume ingredient, with its musky, leathery smell.

It’s a warm, slightly spicy leather scent, with a lot of Mediterranean herbs, most notably clary sage and thyme, that most of us would probably associate with hot, rocky mountainsides in southern France and Greece. My nose isn’t yet sensitive enough to identify them, but it also apparently contains labdanum (derived from two different species of Cistus, another Mediterranean shrub), as well as sandalwood and patchouli, which presumably add to the slightly hippyish warmth of the scent.

Antaeus became a big best-seller in the early 1980s initially, it seems, among gay men, and with its hints of sex and leather it’s easy to see why. Chanel itself tapped into this trend in 1983 with a delightfully pervy advert (pictured), whose subtext I can leave to your imagination.

Antaeus became a big best-seller in the early 1980s initially, it seems, among gay men, and with its hints of sex and leather it’s easy to see why. Chanel itself tapped into this trend in 1983 with a delightfully pervy advert (pictured), whose subtext I can leave to your imagination.

But gay men, as we’ve often been told, are classic early adopters, and these days Antaeus is just as likely to attract anyone who enjoys a rich and complex scent. It’s long been one of my favourites, for its warmth and easy appeal, but I love its darker origins too: sex (and history) in a bottle.

Comme des Garçons

Eau de Parfum

12 November, 2014

Christmas is coming, and as a long-standing fan of over-indulgence I’m thoroughly looking forward to getting fat on Christmas pudding with brandy butter, washed down with a large glass of Harvey’s Bristol Cream, ideally in front of a roaring log fire. Alternatively I could just blow my own socks off with a generous splash of Comme des Garçons’ delicious Eau de Parfum a.k.a. Christmas in a bottle.

Christmas is coming, and as a long-standing fan of over-indulgence I’m thoroughly looking forward to getting fat on Christmas pudding with brandy butter, washed down with a large glass of Harvey’s Bristol Cream, ideally in front of a roaring log fire. Alternatively I could just blow my own socks off with a generous splash of Comme des Garçons’ delicious Eau de Parfum a.k.a. Christmas in a bottle.

Launched in 1994, this was the Japanese cult fashion brand’s first foray into perfume, but if there was nothing unusual about that, it’s rare for a first perfume to make such a big impression. Partly it was the design of the bottle, a slightly egg-shaped oval with an off-centre cap and no obvious way to stand it up.

That might sound a bit annoying, but I think it’s one of the most stylish and sophisticated perfume-bottle designs of the last 20 years. Eccentric it may be, but Comme des Garçons founder Rei Kawakubo’s design is so sleek and refined that it makes most other perfume bottles look cheap and tawdry by comparison.

The Sniff Box is about the scent, though, and what a scent this is. Created by Derby-born perfumer Mark Buxton, it’s not for the shy or faint of heart, for this is one of those fragrances that carries everything (and everyone) before you. The first thing you smell is cloves – or rather clove oil: in fact this is a distinctly oily concoction, for among the other ingredients are nutmeg oil, cinnamon-bark oil, cardamom oil, geranium oil and coriander oil. To me it even feels slightly oily on the skin, which gives it an added touch of luxury and also sets it apart from the vast majority of alcohol-based fragrances.

With ingredients like those it could hardly be anything other than spicy, but Mark Buxton cleverly added a touch of the resinous, smoky smell of incense with cedarwood, labdanum and styrax. The result is wonderfully rich and strange, and though some people find it overpowering, to be overpowered like this is like drowning in a butt of Malmsey: what a way to go!