Tagged With ‘sexy’

Bulgari

Black

10 July, 2015

One of the problems with perfume is that there are far too many to choose from. Every year brings more new launches than the year before, and every year the choice becomes more bewildering.

One of the problems with perfume is that there are far too many to choose from. Every year brings more new launches than the year before, and every year the choice becomes more bewildering.

Yet look (or rather smell) more carefully and it soon becomes clear that the vast majority of scents smell boringly similar to each other. Perfume companies on the whole like to play it safe, since it costs a lot of money to launch a new one and failure can be very costly.

So you can bet your bottom dollar that the minute a new fragrance starts to sell really well, a hundred imitations will start appearing on the shelves. Of course it could all be coincidence, or something in the air, but it’s amazing how many perfumes smell virtually identical, even when their branding and their marketing is poles apart. (Want to do a little experiment? OK, follow my friend Roja Dove’s suggestion and try comparing Angel Men with Bleu de Chanel…)

Yet once in a while a really new fragrance does come along, something that stands out from the crowd. Some of them go on to become best-sellers; others don’t. Some of them are crowd-pleasers. Others are wonderful but weird. And few are weirder or more wonderful than Bulgari Black.

Launched in 1998, this was Bulgari’s first perfume for men. It was created by a very talented perfumer called Annick Menardo, who works for the multinational fragrance company, IFF. Now, I’m not a great believer in that tired old cliché that scents can transport you instantly back to a specific moment in your childhood or the like, but the first time I smelled Bulgari Black that’s exactly what happened to me.

I wasn’t transported back to my mother’s knee, though, or to the smell of laundry on a winter’s day. Bulgari Black took me somewhere far more interesting: to the toxic but weirdly sexy 1970s smell that greeted you when you opened the door of a car that had been sitting for too long in the summer sun – of hot PVC, of black plastic car seats that stuck to your legs when you got in.

I think it’s an amazing perfume: the olfactory equivalent of a Helmut Newton photo-shoot, simultaneously erotic and slightly repellent, though I’m still not sure I could actually wear it. But for anyone who loves fast cars and the smell of burning tyres then maybe this is the perfume for you.

Annick Goutal

Sables

5 February, 2015

Once you’ve smelled a lot of perfumes you start to realise when a scent is cheap and nasty – even on the occasions when it’s got a huge advertising budget and everyone seems to be buying it. (Why? Well, a lot of people still get swept up by advertising, but you can be fairly sure they’ll only buy it once.)

Once you’ve smelled a lot of perfumes you start to realise when a scent is cheap and nasty – even on the occasions when it’s got a huge advertising budget and everyone seems to be buying it. (Why? Well, a lot of people still get swept up by advertising, but you can be fairly sure they’ll only buy it once.)

But even among the most brilliantly put-together perfumes each person’s individual reaction counts for a lot. Smell taps in to such deeply rooted – and often subconscious – memories and associations for each of us that two people can have completely different gut-reactions to the same scent.

And not only that: it actually smells completely different to each of them, even though their brain is presumably processing the same elements in a fairly similar way. Most scientists seem to agree that, unless we suffer from particularly severe sight problems, the way I see Hèrmes orange is almost certainly the same as the way you see it.

Smell, though, appears to work in a rather different manner. We may well smell the same scents in the same objective way, but the personal associations that specific scents have for us seem to be more powerful than what we actually smell – conceivably for the simple reason that we have such trouble describing them in words.

Here’s a perfect example. Sables was first launched by the late, great French perfumer Annick Goutal in 1985, and though it was withdrawn from the UK market some time ago in one of those mysterious overnight disappearances that give the perfume industry its faint whiff of Stalinism, it can still be bought online and abroad.

Sables is one of my all-time favourite fragrances. Though its name is meant to evoke the high-summer sexiness of sun-baked sand, this fantastically rich, sweetly luxurious scent smells, to me, of all the best things about Christmas – vintage oloroso sherry, mince pies, the delicious heat of an applewood log fire, flaming brandy, Christmas pudding… All very positive associations, as far as I’m concerned.

I’d be the first to admit that Sables is strong stuff, best suited to opulent winter evenings; apply it too liberally and, like Guerlain’s L’heure bleue or Chanel’s No22, it can easily become overpowering. But while I can imagine choking on No22 in too high a concentration, to be overcome by Sables would, for me at least, be like drowning in a butt of Malmsey – frankly not a bad way to go.

To a friend who knows at least as much about perfume as I do, though, Sables has an unattractively medicinal smell with none of the enchanting connotations that give it such a deep and lasting appeal for me. I can (kind of) see what he’s getting at, and if I try hard I can just about identify a hint of cough-mixture about it, but for some reason that association, in my mind, is completely drowned out by all the good stuff I’ve already mentioned.

The moral? I’m not sure there is one, but I guess it’s always good to remember there’s no guarantee that everyone is going to share your passion for a particular perfume, no matter how wonderful it smells to you.

Chanel

Antaeus

8 December, 2014

When I first started thinking about The Sniff Box, I wondered how I could make it look different from other perfume blogs. I knew I’d have no problem with the overall look, thanks to my super-talented friend, Leanda Ryan, whose design perfectly reflects the idea of ‘perfume in plain English’.

When I first started thinking about The Sniff Box, I wondered how I could make it look different from other perfume blogs. I knew I’d have no problem with the overall look, thanks to my super-talented friend, Leanda Ryan, whose design perfectly reflects the idea of ‘perfume in plain English’.

But illustrating individual perfumes is a problem, as you’ll gather if you look at other perfume sites on the interweb. The obvious thing to do is to use a ‘pack shot’, generally supplied by the brand in question: it’s what the brands like as that’s how they want you to see their scent, but how many times do you want to see the same cheesy photograph?

The trouble is, if you don’t use a photo of the bottle, what can you use instead? How do you illustrate something you can smell but can’t actually see? It’s interesting to check out what other people come up with, but given that few bloggers can afford to commission photography or illustration, they’re generally stuck with stock shots of things like perfume ingredients – a sprig of lavender, say, or a twist of lemon – which are as cheesy as the pack shots they’re trying to avoid.

It took a while, but finally it struck me: since I can draw, after a fashion, why not draw my own illustrations? And that’s how I began.

All of which is a roundabout way of saying that, when I was trying to draw my bottle of Antaeus this morning, it gradually dawned on me that it is one of the most beautiful perfume bottles I know. It’s also one of the simplest: a tall, square, black-glass container that, if you took away the classy sans-serif Chanel lettering, would bear a more-than-passing resemblance to sinister monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Designed (or at least commissioned) by Chanel’s long-standing artistic director, Jacques Helleu, and launched in 1981, Antaeus was a kind of dark-side twin to the brand’s only other men’s fragrance at that time, Pour Monsieur (launched way back in 1955). Their bottles may be almost identical in shape, but Pour Monsieur is as cool and transparent as Antaeus is brooding and mysterious, and that reflects the fact that they’re very different scents.

Pour Monsieur is a refined, impeccably discreet fragrance: perfect in its way but perhaps (dare one whisper it?) just a tiny bit dull. Antaeus, by contrast, is a dark sexy scent that was launched just as the disco era crashed and burned: the same year Ian Schrager and Steve Rubell sold out of Studio 54 and the big disease with a little name first reared its ugly head.

Antaeus (the scent) was created by Chanel’s much-fêted in-house perfumer, Jacques Polge, in collaboration with François Damachy, now head of fragrance at Dior). As suggestive as Pour Monsieur is safe, its sexiness comes from castoreum, derived from a secretion extracted from beaver wee (I kid you not), which despite its revolting origins becomes, after careful treatment, a potent perfume ingredient, with its musky, leathery smell.

It’s a warm, slightly spicy leather scent, with a lot of Mediterranean herbs, most notably clary sage and thyme, that most of us would probably associate with hot, rocky mountainsides in southern France and Greece. My nose isn’t yet sensitive enough to identify them, but it also apparently contains labdanum (derived from two different species of Cistus, another Mediterranean shrub), as well as sandalwood and patchouli, which presumably add to the slightly hippyish warmth of the scent.

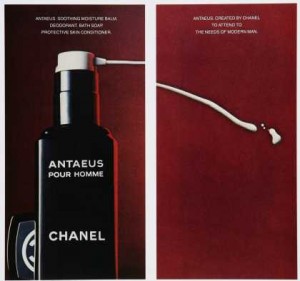

Antaeus became a big best-seller in the early 1980s initially, it seems, among gay men, and with its hints of sex and leather it’s easy to see why. Chanel itself tapped into this trend in 1983 with a delightfully pervy advert (pictured), whose subtext I can leave to your imagination.

Antaeus became a big best-seller in the early 1980s initially, it seems, among gay men, and with its hints of sex and leather it’s easy to see why. Chanel itself tapped into this trend in 1983 with a delightfully pervy advert (pictured), whose subtext I can leave to your imagination.

But gay men, as we’ve often been told, are classic early adopters, and these days Antaeus is just as likely to attract anyone who enjoys a rich and complex scent. It’s long been one of my favourites, for its warmth and easy appeal, but I love its darker origins too: sex (and history) in a bottle.